| Testimonies

& Critics

The Nijinsky Galas at London (II)

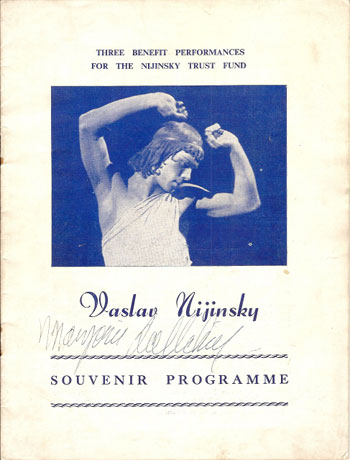

Under this same title we have referred before to this dancing event, made at the Empress Hall in London on November 1949. However, with a certain effort, we have now been able to obtain an original program from those Galas, which indeed makes us very proud.

To have in our hands an original program from that historical artistic event is almost incredible, for such an issue shall never be repeated again and remains unique for the fortunate people who attended to it, and even to those of us who can only imagine it. To see Chauviré, Toumanova, Massine, Babilée, Skouratoff, Skibine and Tallchief dancing together on the same soirée must have been also incredible. That’s the reason why we want to refer to this item once more; and to state on these pages the extraordinary value of the information and illustrations it brings us, we transcribe it below as it figures on such souvenir programme:

|

|

The cover of the program, with Marjorie Tallchief’s autograph

|

|

|

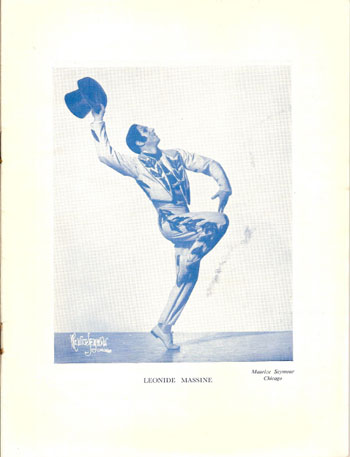

Cyril Beaumont’s commentary on Vaslav Nijinsky, which we transcribe below

|

|

|

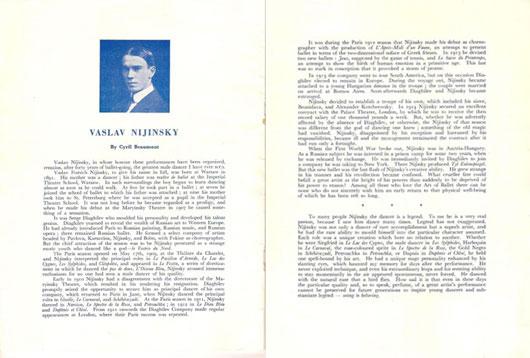

Tamara Toumanova (photo: Duncan Melvin)

|

|

|

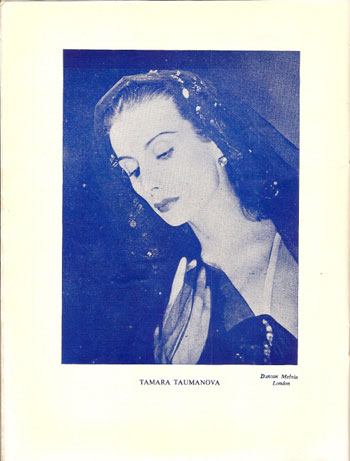

Léonide Massine (photo: Maurice Seymour)

|

|

|

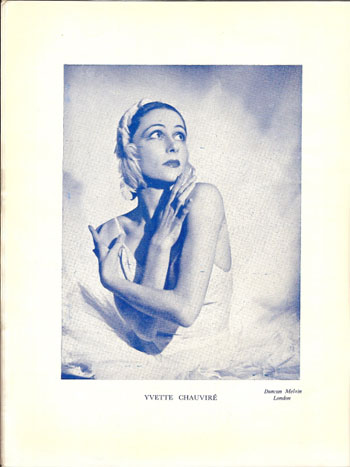

Yvette Chauviré (photo: Duncan Melvin)

|

|

|

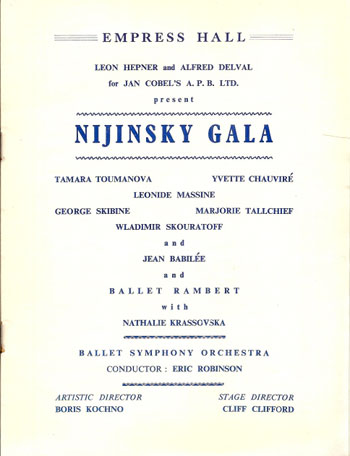

The glorious cast of the Nijinsky’s Galas in London, November 1949

|

|

|

The 3 parts of the soirée’ s program

|

|

|

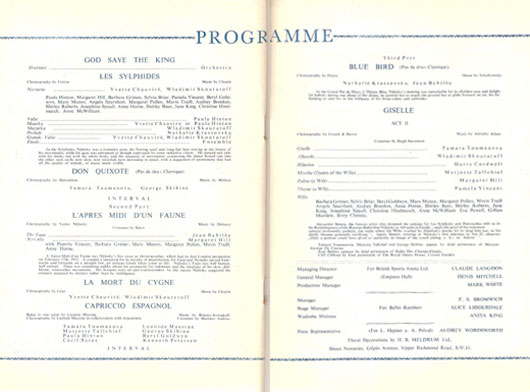

Jean Babilée (photo: Roger Wood)

|

|

|

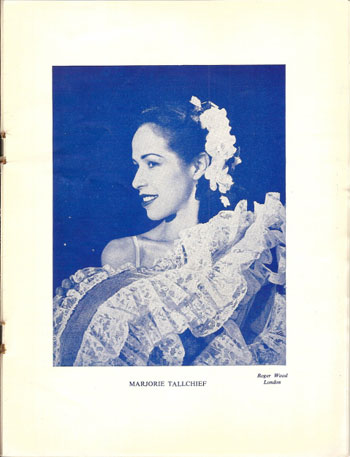

Marjorie Tallchief (photo: Roger Wood)

|

|

|

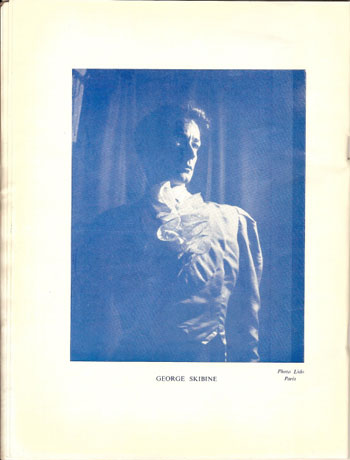

George Skibine (photo: Serge Lido)

|

|

|

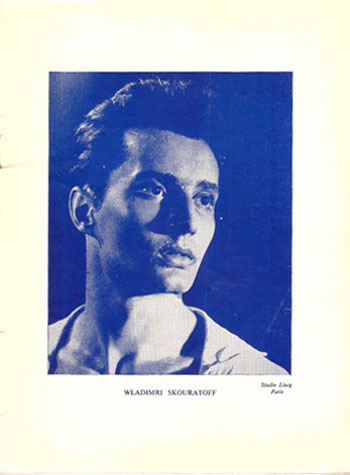

Wladimir Skouratoff (photo: Studio Liseg)

|

VASLAV NIJINSKY by Cyril Beaumont

Vaslav Nijinsky, in whose honour these performances have been organized, remains, after forty years of ballet-going, the greatest male dancer I have ever seen.

Vaslav Fomich Nijinsky, to give his name in full, was born at Warsaw in 1891. His mother was a dancer; his father was maître de ballet at the Imperial Theatre School, Warsaw. In such surroundings the boy began to learn dancing almost as soon as he could walk. At five he took part in a ballet; at seven he joined the school of ballet to which his father was attached; at nine his mother took him to St. Petersburg where he was accepted as a pupil in the Imperial Theatre School. It was not long before he became regarded as a prodigy, and when he made his debut at the Maryinsky Theatre in 1907 he caused something of a sensation.

It was Serge Diaghilew who moulded his personality and developed his talent genius.

Diaghilew yearned to reveal the wealth of Russian art to Western Europe. He had already introduced Paris to Russian painting, Russian music, and Russian opera; there remained Russian ballet. He formed a select company of artists headed by Pavlova, Karsavina, Nijinsky and Bolm, with Fokine as a choreographer. But the chief attraction of the season was to be Nijinsky presented as a strange exotic youth who danced like a god – le Vestris du Nord.

The Paris season opened on May 17th, 1909, at the Théâtre du Chatelet, and Nijinsky interpreted the principal roles in Le Pavillon d’Armide, Le Lac des Cygnes, Les Sylphides and Cléopâtre, and appeared in Le Festin, a series of divertissements in which he danced the pas de deux L’Oiseau Bleu. Nijinsky aroused immense enthusiasm for no one had seen a male dancer of his quality.

Early in 1910 Nijinsky had a disagreement with the directorate of the Maryinsky Theatre, which resulted in his tendering his resignation. Diaghilew promptly seized the opportunity to secure him as principal dancer of his own company, which returned to Paris in June, when Nijinsky danced the principal roles in Giselle, Le Carnaval and Schéhérezade. At the Paris season in 1911, Nijinsky danced in Narcisse, Le Spectre de la Rose and Petrouchka; in 1912 in Le Dieu Bleu and Daphnis et Chloé. From 1911 onwards the Diaghilew Company made regular appearances in London, where their Paris success was repeated.

It was during the Paris 1912 season that Nijinsky made his debut as choreographer with the production of L’Après-Midi d’un Faune, an attempt to present ballet in terms of the two-dimensional suface of Greek friezes. In 1913 he devised two new ballets: Jeux, suggested by the game of tennis, and Le Sacre du Printemps, an attempt to show the birth of human emotion in a primitive age. This last was so stark in conception that it provoked a storm of protest.

In 1913 the company went to tour South America, but on this occasion Diaghilew elected to remain in Europe. During the voyage out, Nijinsky became attached to a young Hungarian danseuse in the troupe; the couple were married on arrival at Buenos Aires. (*) Soon afterwards Diaghilew and Nijinsky became estranged.

Nijinsky decided to establish a troupe of his own, which included his sister, Bronislawa, and Alexander Kotchetovsky. In 1914 Nijinsky secured and excellent contract with the Palace Theatre, London, by which he was to receive the then record salary of one thousand pounds a week. But whether he was adversely affected by the absence of Diaghilew, or otherwise, the Nijinsky of that season was different from the god of dancing one knew; something of the old magic had vanished. Nijinsky, disappointed by his reception and harrassed by his responsibilities, became ill and the management terminated the contract after it had run only a fortnight.

When the First World War broke out, Nijinsky was in Austria-Hungary. As a Russian subject he was interned in a prison camp for some two years, when he was released by exchange. What crueller fate could befall a great artist at the height of his powers than suddenly to be deprived of his power to reason! Among all those who love the Art of Ballet there can be none who do not sincerely wish him an early return to that physical well-being of which he has been reft so long. (**)

* * *

To many people Nijinsky the dancer is a legend. To me he isa very real person, because I saw him dance many times. Legend has not exaggerated. Nijinsky was not only a dancer of rare accomplishment but a superb artist, and he had the rare ability to mould himself into the particular character assumed. Each role was a unique creation which bore no relation to another. Whether he were Siegfried in Le Lac des Cygnes, the mal dancer in Les Sylphides, Harlequin in Le Carnaval, the rose-coloured sprite in Le Spectre de la Rose, the Gold Negro in Schéhérazadé, Petrouchka in Petrouchka, or Daphnis in Daphnis et Chloé, he held one spell-bound by his art. He had a unique stage personality enhanced by his slanting eyes, which haunted my memory for days after the performance. He never exploited technique, and even his extraordinary leaps and his seeming ability to stay momentarily in the air appeared spontaneous, never forced. He danced with the natural ease that a bird flies. How sad is that even in these days the particular quality and, so to speak, perfume of a great artist’s performance cannot be preserved for future generations to inspire young dancers and substantiate legend – seeing is believing.

(*) Vaslav Nijinsky and Romola de Pulszky were married in Buenos Aires, at Saint Michael’s Church, in 1913.

(**) Vaslav Nijinsky died not long after the Galas in whose honour were organized, in London, on April 1950. He was still interned on a psychiatric hospital.

|